We Might Be Closer To Unlocking Fusion Than We Thought

Bigger is better when it comes to fusion.

Imagine a power source as potent as nuclear power but with no carbon emissions, no dangerous nuclear waste, no risk of nuclear meltdown, and no risk of us ever exhausting the planet’s fuel supply. Well, fusion power promises just this. By replicating the process that powers the Sun, fusion could be the perfect energy source. However, we have spent decades trying to bring this fantastic technology to fruition with no luck. One of the biggest hurdles stopping fusion power from becoming a reality is plasma instability, which has often damaged these reactors beyond repair before they ever get close to producing power. However, recent research suggests this issue could actually solve itself with the next generation of giant reactors like ITER.

As always, let’s start at the beginning. What is fusion?

As I said, nuclear fusion is the process that powers the Sun. In its core, the temperatures are so high e is so intense that hydrogen atoms have enough kinetic energy to overcome the repulsive force that keeps them separate and fuse into a single larger helium atom when they collide. Helium weighs slightly less than two atoms of hydrogen, so there is a bit of spare mass floating around in the form of subatomic particles. These particles can’t physically exist without being attached to protons or neutrons, so they turn into energy and radiate out. Now, if you paid attention in physics class, you’d remember that Einstein’s famous equation E=MC² means that a tiny bit of matter is equal to an utterly vast amount of energy! As such, a single kilogram of hydrogen can produce 177,717 MWh of energy through fusion, or 7.9 times more than a kilogram of pure uranium-235 produces through fission or 14.8 million times more energy than a kilogram of gasoline through combustion! But, unlike uranium or gasoline, fusion doesn’t produce any radioactive waste or climate-destroying emissions. The only by-product is valuable non-radioactive helium gas.

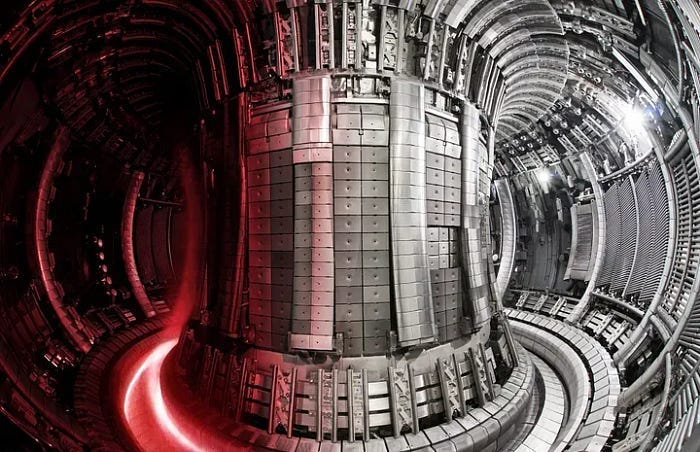

So, how do we replicate this process on Earth? Well, one of the most popular fusion reactor designs is known as a Tokamak. This uses a doughnut-shaped reactor chamber surrounded by superconducting magnets. You see, hydrogen plasma reacts to magnetic fields. So these magnets heat the plasma using the same process as an induction hob whilst also squeezing it. This leads to particle collisions with enough kinetic energy to create fusion!

However, hydrogen plasma is incredibly hard to control, particularly when superheated and under immense pressure. One such type of instability is edge-localised modes (ELMs). ELMs are complex, so I will explain them as simply as possible. At the plasma’s edge, the density gradient is massive, which can cause ripple-like instabilities on the surface of the plasma. These instabilities interfere with how the plasma interacts with the magnetic field and can periodically relax the squeezing force felt by the plasma. When this happens, it is like popping a balloon, and the energy within the plasma is released in the form of vast amounts of heat and an enormous amount of high-energy particles.

This massively reduces the efficiency of the reactor, as a single ELM can cause the plasma to lose up to 20% of its energy. This is a huge problem, as to make a fusion reactor a viable power source, it needs to produce more energy than it consumes to create fusion, something that no reactor is currently close to. But it can also damage the reactor, as all of that heat energy is dumped into the reactor walls, damaging it.

There are many different types of instability, but all of them cause the same efficiency reduction and damage to the reactor. So, if you want to crack fusion power, you must master plasma control and stop instability in its tracks.

Plasma control is insanely complex. The fluid dynamics of such hot, dense plasma are so convoluted and happen so fast that computers and control systems can’t respond fast enough to try and stop them. As such, many scientists are turning to AI to try and predict the plasma, enabling them to stop instability events before they even occur. These systems are effective, but not enough to reduce instability events enough to make the reactors produce more energy than they consume.

But this is where a new study comes in.

This study looked at simulations that showed the plasma behaved differently in larger reactors. You see, all the tokamaks currently operating are small research reactors. But larger tokamaks, such as ITER, are currently being built and are over twice as large as any currently operational tokamak! These larger reactors have more room for the plasma and don’t have a ‘bend’ the plasma around such a tight radius, leading to different plasma dynamics.

The researchers found that these larger reactors contain plasma turbulence in a relatively concentrated area. As such, plasma ejections caused by instabilities don’t ravel out to the reactor wall but, instead, loop back around and rejoin the main plasma body. This means that the plasma doesn’t escape containment despite instabilities, keeping energy within the plasma, dramatically increasing efficiency, and enabling the reactor to run at higher energies with a lower risk of damage.

This won’t render instabilities a non-problem, but instead will mean that these larger reactors will have a far easier time mitigating them with simple plasma control.

So, what does this mean in practice? Well, it means ITER can likely be operated far more efficiently than initially thought. Current estimates suggest ITER will produce ten times the power it takes to run once it has been optimised. If this study is right, it could mean ITER could not only be the first reactor to produce power but also produce enough to be a viable power source! But that is only if these simulations are accurate. Scientists need to do far more studies to double-check if these findings are correct and applicable to ITER.

Thanks for reading! Content like this doesn’t happen without your support. So, if you want to see more like this, don’t forget to Subscribe and help get the word out by hitting the share button below.

Sources: IOP, PPPL, Notebook Check, Will Lockett, Will Lockett